Old timepieces evolution

The first running spring clocks

Some timepieces, such as sun-dials and water-operated watches were known to people from time immemorial. Smaller individual timepieces became possible only after the running spring was invented. It was at the beginning of the 16th century that Peter Heinlen from Nuremberg made several spring clocks. Soon they began to be produced in Augsburg and Prague.

Some timepieces, such as sun-dials and water-operated watches were known to people from time immemorial. Smaller individual timepieces became possible only after the running spring was invented. It was at the beginning of the 16th century that Peter Heinlen from Nuremberg made several spring clocks. Soon they began to be produced in Augsburg and Prague.

The centres of watch-making sprang up in the 16th century in Blois, Paris, Lyons, London, Amsterdam and other West European cities. Spring watches became smaller and smaller, so that in the second half of the 16th century miniature pocket watches were made, but the title “pocket” was only conditional as at that period and later these watches were worn on chains hanging on one’s neck. The earlier samples of pocket watches had only one hour hand. Time was marked in roman numerals which were placed on the metal plate of the face. There was no face glass yet. The hand was protected by a blind lid which was often made of rock crystal or topaz as well as the whole watch.

The centres of watch-making sprang up in the 16th century in Blois, Paris, Lyons, London, Amsterdam and other West European cities. Spring watches became smaller and smaller, so that in the second half of the 16th century miniature pocket watches were made, but the title “pocket” was only conditional as at that period and later these watches were worn on chains hanging on one’s neck. The earlier samples of pocket watches had only one hour hand. Time was marked in roman numerals which were placed on the metal plate of the face. There was no face glass yet. The hand was protected by a blind lid which was often made of rock crystal or topaz as well as the whole watch.

Samples of the described piece are watches by German masters Peter Heele and French master Paul Cuper*.

* Paul Cuper was from Liège (Belgium) en went to live in Blois. He was not a Frenchman. technically he was citizen of Liège. A prince-bishopry in the German empire (although they spoke Dutch and French overthere. his name suggests he spoke Dutch)

When the watch case was made of metal, e.g. of gilt copper, the lid was decorated with an openwork design which adorned the object and at the same time made it possible to see the movement of the hand through the openings. Although glass was widely used beginning with the mid-17th century, one can see pieces with lids like that even dating from the second half of the 17th century, e.g. a watch made by French master Guex in the shape of a tambourine.

Abbess’ watch (late 16th)

In early pocket watches a variety of materials, shapes and types of decoration were employed. They were octagonal, oval, rectangular, book-shaped, or resembled flower buds and animals. Watches made in the form of a skull or a cross were to remind their owner and people who surrounded him of the transiency of life. The cross-watch is believed to have been invented in mid-16th century by French masters. It is known as the abbess’ watch and was meant for clergymen. They were usually decorated by scenes from the life of Christ or from the Bible.

Timepieces of the Renaissance

Pocket watches were the fruit of cooperation between watchmakers and jewellers. In designing their engraved, niello and enamel patterns and figure compositions that cover the items, masters made use of engravings. The decoration had to follow the style of the applied art of the period.

Pocket watches were the fruit of cooperation between watchmakers and jewellers. In designing their engraved, niello and enamel patterns and figure compositions that cover the items, masters made use of engravings. The decoration had to follow the style of the applied art of the period.

There are an early 17th-century watch with pictures of rare beauty showing the allegories of Wisdom and Justice, birds and flowers executed in the typical technique of the period, that of cut enamel. The outer side of the shutters bears a cameo on a shell with the portrait of Emperor Ferdinand II. This watch, a wonderful piece of the Renaissance style, comes from Count Musin-Pushkin’s collection. The engraved decor on the watch by Parisian master Barberet is also done in the Renaissance tradition.

There are an early 17th-century watch with pictures of rare beauty showing the allegories of Wisdom and Justice, birds and flowers executed in the typical technique of the period, that of cut enamel. The outer side of the shutters bears a cameo on a shell with the portrait of Emperor Ferdinand II. This watch, a wonderful piece of the Renaissance style, comes from Count Musin-Pushkin’s collection. The engraved decor on the watch by Parisian master Barberet is also done in the Renaissance tradition.

Watch mechanism accuracy

In the course of the 17th century the centre of watch production in Europe shifted from town to town for some special reasons. The events of the Thirty Year’s War (1618-48) undermined the former power in watchmaking of some German cities like Nuremberg and Augsburg. In early 17th century French watchmakers had no equals in Europe. But after the abolishment of the Nantes edict in 1685, many well-known Protestant masters left France and emigrated to England and Switzerland where they promoted the revival of watch production. By 1700 these countries became the world centres of watch making.

The 17th century brought about great, changes in the watch mechanism. In 1657, Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens first applied the pendulum theory to regulate the clock operation which ensured its accuracy. After 1650 the minute hand appeared and so did the second round of arabic numerals to indicate the minutes on the face plate. In the second half of the 17th century pocket watches acquired a round shape which is more familiar to us. This however does not mean that all watches produced at that time had a minute hand and were round in shape. There is a wonderful watch by Parisian master Auguste Bretaunneau: it is of square shape, with one hand and a crystal lid instead of a face glass which was already usual for the second half of the 17th century. The watch is decorated with blue enamel, diamonds and a laid-on gold floral pattern.

Spiral spring in the watch mechanism

In the last quarter of the 17th century they began to use a spiral spring in the watch mechanism, which changed its form: it became more concave, onion-shaped.

In the last quarter of the 17th century they began to use a spiral spring in the watch mechanism, which changed its form: it became more concave, onion-shaped.

That was also the time when special cases were made to carry the watches, and greater became the part played by goldsmiths.

Antique timepieces show very well how masters liked to decorate all details of a piece, including the head of the time-setting mechanism, as well as the plate that covers the mechanism and that is called “Lichinka”.

“Lichinkas” were usually decorated with an openwork design, but very often we can see blind plates covered with pictures in painted enamel invented by Jean Toutin and which became very popular in the 1630s.

Timepieces with enamel plates

There are some very interesting timepieces with such enamel plates. It is an English watch showing a lady painted in colours characteristic of French enamellers’ manner, and a Dutch watch by master H. Petri with a beautifully done composition Susannah and the Elders.

There are some very interesting timepieces with such enamel plates. It is an English watch showing a lady painted in colours characteristic of French enamellers’ manner, and a Dutch watch by master H. Petri with a beautifully done composition Susannah and the Elders.

By early 18th century French-painted enamels had won renown all over Western Europe, and English watchmakers encased their mechanisms in cases commissioned to French enamellers. In decorating their works the enamel artists made use of their own compositions or reproduced other artists’ works.

Jewelry watches

In the first quarter of the 18th century the leadership in enamel painting was taken over by Switzerland. The work of Swiss enamellers of the period can well be seen in the works of master Hanhart; their surface is decorated with exquisitely done pictures from Greek mythology.

But it was not only painted enamel that decorated watches in the 18th century. Gems were also an important component in their ornamentation. Thus the face of the watch by English master Peter Par-quot is covered with diamonds shining against their blue enamel background. Gems were also placed on the crystal face.

Rococo style old watches

In the 1730s, the Rococo style dominated all kinds of art: applied art in particular. The rich fantasy of the jewellers working in this intricate style was first and foremost demonstrated in the variety of materials they used. Watches were made of gold, silver, mother-of-pearl and semi-precious stones. Their surface was stamped with fanciful patterns, their main element being a shell-shaped curl.

In the 1730s, the Rococo style dominated all kinds of art: applied art in particular. The rich fantasy of the jewellers working in this intricate style was first and foremost demonstrated in the variety of materials they used. Watches were made of gold, silver, mother-of-pearl and semi-precious stones. Their surface was stamped with fanciful patterns, their main element being a shell-shaped curl.

Watches became a true costume decoration. Starting with the 1730s they were worn on a special chain — chatelaine which consisted of several links. The chatelaine was fixed to the costume belt with a hook. The watch case and the chatelaine were made of the same material and decorated with the same design. The chain and the watch case by anonymous English master are made of green heliothrope. The graceful watch-snuff-box by London watchmaker Telliap is also made of heliothrope in the Rococo style.

Classical rare timepieces

The Rococo style is replaced by Classicism in the 1760s, it is characterised by serene and austere forms and symmetrical design. Flower garlands, classical vases and pearl framing are elements of new ornamentation that can be traced in the decor of the watch made by Danish master Sicers.

The Rococo style is replaced by Classicism in the 1760s, it is characterised by serene and austere forms and symmetrical design. Flower garlands, classical vases and pearl framing are elements of new ornamentation that can be traced in the decor of the watch made by Danish master Sicers.

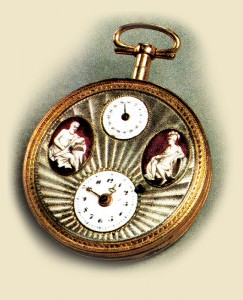

Theatre-watch

In the last third of the 18th century a theatre-watch was a very fashionable trinket. They were mostly produced by French and Swiss masters. The museum collection possesses a watch like that. Dancing couples are shown in an architectural interior with mirrors in the background. When music began playing inside the mechanism the pairs began to waltz while the figurines of the conductor and the harp-player moved their hands.

In the last third of the 18th century a theatre-watch was a very fashionable trinket. They were mostly produced by French and Swiss masters. The museum collection possesses a watch like that. Dancing couples are shown in an architectural interior with mirrors in the background. When music began playing inside the mechanism the pairs began to waltz while the figurines of the conductor and the harp-player moved their hands.

Breguet watches

By the second half of the 18th century the watch mechanism got more sophisticated, and it became thinner and more flat. Abraham Louis Breguet, a well-known master and friend of Marat — leader of the French Revolution, worked a lot at the modernisation of timepieces. Among the watches by Breguet kept in the Museum collection especially interesting as to its decoration is the watch with blue transparent enamel on guilloche background.

By the second half of the 18th century the watch mechanism got more sophisticated, and it became thinner and more flat. Abraham Louis Breguet, a well-known master and friend of Marat — leader of the French Revolution, worked a lot at the modernisation of timepieces. Among the watches by Breguet kept in the Museum collection especially interesting as to its decoration is the watch with blue transparent enamel on guilloche background.

Almost all watches of the late 18th century were made without cases. Double and triple cases remained popular only in England. But even there watches with several lids began to appear in the late 1820s, e.g. works by the English firm “Dol-ter”.

At the beginning of the 20th century Swiss watchmakers went over to semi-automatic production. They produced up to 100 thousand items a year and sold them all over the world. Watches became mass produced items.

In the course of the 19th century watches were technically improved. Pocket watches no longer employed keys for setting the mechanism but heads. It was invented by Englishman T. Prestu in 1820, and the Swiss A. Philipps began to use this head not only to set a watch running but also to set the time. The third, second, hand became usual in the watches of the second half of the 19th century.

Despite mass production, the best samples of watchmaking combined high technical qualities with exquisiteness and refined decoration.

Despite mass production, the best samples of watchmaking combined high technical qualities with exquisiteness and refined decoration.

| Old pocket watches with small gun » |